Stage 3: Teaching Comprehension - The Theory

A Brief History of Comprehension Instruction.

Traditionally, comprehension skills were developed by asking the learner lots of questions. It was assumed that if we the teacher modelled the higher order thinking that was required to understand text, then eventually the reader would learn to do that for themselves.

In the 1990s we became aware of comprehension strategies and have since generated long lists of metacognitive strategies that are often taught in a haphazard manner with varying degrees of impact on our learners.

“Most approaches to comprehension instruction revolve around equipping the learner with many strategies (intentional actions students can use during and after reading to guide their thinking) which the student then selects from and applies to problem solve comprehension issues.”

We think there is a Sharper way of developing skilled Comprehenders.

Recent Research (The Science of Reading)

The last two decades have provided us with many new insights into the way the brain functions when reading and we now have increasingly complex models which describe this process. SharpReading aligns well with these models. We have paid particular attention to the research which identifies how the brain goes about the task of making sense of the squiggles on the page.

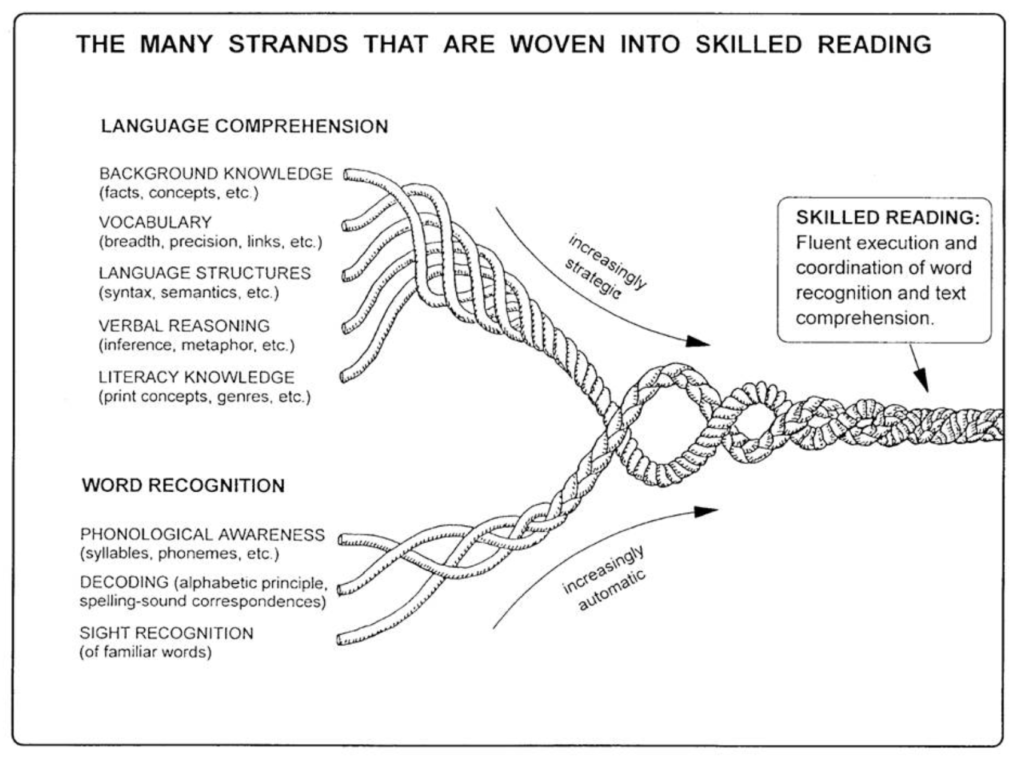

But for the sake of simplicity we are going to base our comments here on one particular model that has stood the test of time, Scarborough’s Rope from 2001, which provides an excellent and not overwhelmingly complex framework for comprehension instruction.

Scarborourgh's Rope (2001)

As you can see, the two distinct parts of the rope demonstrate a well understood distinction in the skill sets required to be a skilled reader.

The Need to Recognise a Developmental Progression

The model highlights the need for developmental progression as the reader moves from left to right towards being a Skilled Reader.

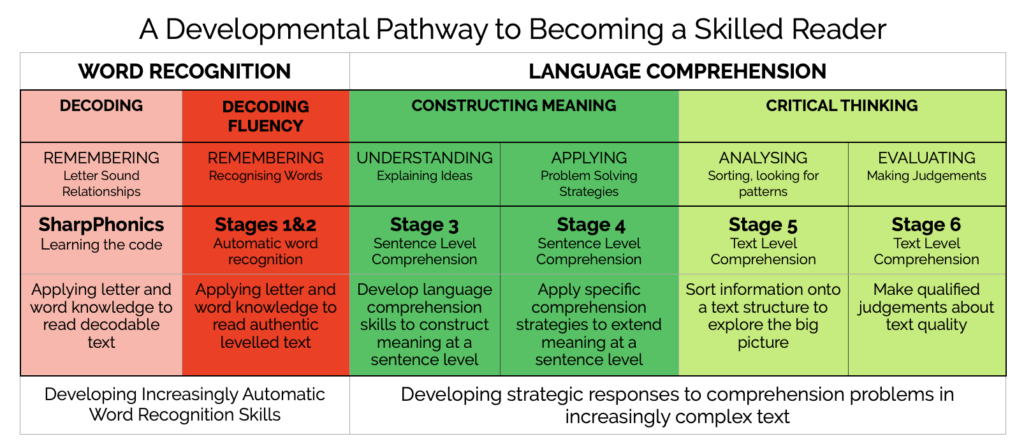

Word Recognition Skills

The starting point of any approach to reading instruction must be to develop word recognition skills. It must be noted that reading is not a naturally acquired skill like walking or talking. It is a man-made construct and as such requires much drilling in the use of a code that, once learned and mastered, becomes increasingly automatic. Developing this decoding fluency is the focus of SharpReading Stages 1&2.

Research on cognitive loading has established that developing automatic word recognition requires an enormous amount of cognitive energy. It is only as the reader approaches decoding fluency that the brain is freed up to focus on text comprehension.

Language Comprehension Skills

Having achieved decoding fluency (a measure of automatic word recognition) the instructional focus can now turn to these language comprehension skills, the other significant rope in Scarborough's model.

This is the focus of Stage 3 and provides the foundation for Stages 4-6.

This is a quite different skill set to the Word Recognition skill set in that it has been developing intuitively from birth.

BACKGROUND KNOWLEDGE - The child gains understanding of the world around them as they experience it and interact with it.

VOCABULARY - They learn words to label objects and their experiences and store these in their long term memory. The average 10 year old has 10,000 words locked away.

LANGUAGE STRUCTURES - The child begins to understand how these words are put together to communicate ideas.

VERBAL REASONING - They learn to sift through these words and sentences and make judgments about the subtly of meaning. They learn how to 'read between the lines' (make inferences) and begin to distinguish between the literal and symbolic use of language.

LITERACY KNOWLEDGE - As they are exposed to the language of written text they decern the difference between spoken and written language and different genres and writing styles.

Skills or Strategies?

Here I think it is important to make a distinction between comprehension skills and the comprehension strategies mentioned earlier.

A musician practises their craft until it is an automatic response, something they no longer have to consciously think about. This is the definition of a 'skill'. These five aspects of language comprehension require that sort of automatic response, the development of language comprehension 'skills'. This is quite different from the teaching of 'intentional actions students can use during and after reading to guide their thinking' (strategies).

We introduce strategies in Stages 4-6, but in Stage 3 we want to polish the use of these language comprehension 'skills'. If we extend the analogy of the musician to that of an orchestra, we could say that the highly skilled comprehender combines the use of these skills in much the same way as an orchestra performs. The background knowledge could be likened to the string section, vocabulary the woodwinds, verbal reasoning the brass section etc. At different times they have different roles in the piece that is being played but they are all combine to create a harmonious result.

The brain research tells us that it is the application and flexible collaboration of these skills that determines the level of comprehension or meaning that the reader will extract from any text they are reading.

The ability to 'be the orchestra' that our students will bring with them as they present themselves in our classrooms has been 5-7 years in the making. It will vary considerably from student to student depending on their innate cognitive ability and the experiences of the world and exposure to text that they have accumulated.

Our very good readers may well have intuitively developed some collaborative use of these skills. However in my experience, and by their own admission, even the more able readers tend to skate over the meaning of what they are reading and 'grab a bit here and a bit there' without attending to the detail.

We refer to this as a passive reader mindset; great decoders, fast readers but unfamiliar with deep processing of text. The orchestra has some sections that need polishing.

Others, while reasonable decoders, have little awareness of processing the meaning of what they have read and are dependant on someone asking them questions to initiate constructive thought. A very limited orchestra.

So, how do we develop the orchestra?

What not to do

A natural response would be in-depth teaching of these language comprehension strands; inferencing, grammar, language features, genre and build vocabulary and general knowledge, and then hope that the learner can transfer what they have learned into their construction of meaning as they read.

Of course there will be some spillover from this instruction - students need to understand conjunctions (connectors of ideas within sentences) and an understanding of idiom and figures of speech is going to be helpful.

But there are two important considerations.

1) How do we put that together into a meaningful, coherent instructional reading program? We are back to 'a bit of this and a bit of that' teaching, hoping it will all come together and transfer into what the reader does WHEN they are reading.

2) The act of comprehension requires great cognitive flexibility to meet the unique challenges in every sentence rather than an ability to apply a set of rules. The landscape changes with every sentence so do the range of language comprehension skills that need to be applied.

Here is an example. "Denise was stuck in a jam and she was worried what her boss would say."

How do we apply the Language Comprehension strands to understand what is going on ion this sentence.

Vocabulary knowledge provides the building blocks of comprehension, but it’s not just a matter of being able to read the words. Here the word jam refers to traffic, not the fruit preserve. The unfamiliar word Denise has to be recognised as a name, and there is the need to analyse words which appear in a complex form, such as worried.

Language structures - Causal connections need to be made within the sentence to understand that she and her in the second part of the sentence refer to Denise in the first sentence.

Verbal Reasoning - to fully understand the action inferences will be made based on the readers background knowledge. Denise was probably on her way to work but was running late because of heavy traffic. How does she travel? Is she a car or on a bus. Perhaps she has been late several times recently and is thus especially worried about there boss's reaction; maybe she is worried because she will be late for a meeting.

These are potential elaborations that are licensed by this particular sentence.

Our Solution - Unpacking Sentences

We think, given the lesson time constraints in our classrooms, that the best way to develop mastery of these skills is to provide a simple structured routine that allows the learner to have a go at integrating this skill set again and again and again.

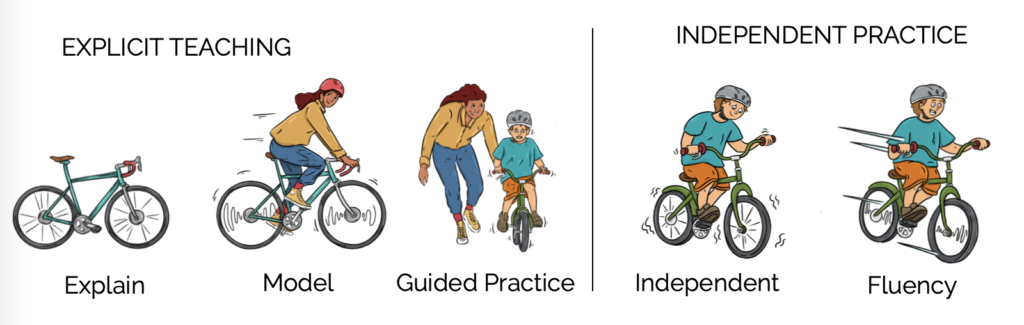

Our routine provides the opportunity for explicit teaching (Explain, Model, Guided Practice) of any aspect of the Language Comprehension domain, but the main focus is on Independent Practice of Unpacking Sentences. This is the chance to learn by DOING it. Integrate all the strands. Get the orchestra playing! The musician learns much more from having to collaborate than by practising a part in isolation.

"Can you convince me that you know what is going on in that sentence?" forces the reader to monitor their comprehension and attend to the bits they don't get. By carefully selecting the level of text difficult we ensure that the comprehension challenges they face are manageable and they can problem solve their way out of them, gaining confidence and satisfaction from their newly acquired comprehension skills.

The Key to Training the Brain: Say it out aloud

With all our SharpReading stages, oral sharing of the thinking required to unpack a sentence allows the speaker to see how blurred their thinking is and then sharpen it. Vague mental responses float around in the mind while reading is taking place. When the reader is asked to verbalise their thinking, a different part of the brain is activated which facilitates the transfer of information from short term memory into long term memory and helps to develop strong thinking pathways and robust active reading habits.

How about a Start-Up Webinar or Workshop?

While the ONLiNE Course will provide you with everything you need to become a fluent Stage 3 SharpReading teacher, attending a start-up event always helps kick start new learning.

Teachers appreciate the opportunity for face-to-face interaction as we outline the research and the pedagogy behind our approach to reading instruction and then provide modelling and practice of our unique guided reading routines.

At the end of the day you should walk away feeling very confident about implementing our routines in your classroom the very next day.

Stage 3 ONLiNE Course PLUS Start-Up Webinar (COST: NZ $155 + GST)

For those who don't have a workshop scheduled for their area or have a restricted PD budget, we set aside two weeks per term for Start-Up Webinars which allow you to take part in a start-up event from your own school (or home).

CLICK HERE for a list of upcoming Stage 3 Webinars.

Stage 3 ONLiNE Course PLUS Start-Up Workshop (COST: NZ $195 + GST)

Contact us to organise a TOD workshop in your school.

When are students ready for Stage 3?

Students are ready to start Stage 3 when they are 'fluent decoders'.

Decoding and Comprehension compete for available short term memory and decoding will always trump comprehension. Therefore it is important that a certain level of decoding fluency is achieved (the decoding process is sufficiently automated to leave space in the head for other things) before asking the reader to focus their cognitive energy on some heavy duty constructing of meaning.

The criteria for moving on to Stage 3

- The reader must demonstrate reasonable fluency at a reading age of 7 or above. That means a good flow as they are reading, not hesitant word by word decoding.

- The reader must have an efficient word attack strategy so they can sound out and chunk unfamiliar / multisyllabic words which start appearing in the text they are reading at around a reading age of 7 years.

- The reader must be monitoring their reading and self correcting miscues especially visual clues ("That doesn't look right!").

- The reader must be able to hold onto the gist of the sentence - they are using the new found space in their heads to ‘hold onto meaning’ not necessarily construct it for themselves.

Students in Junior Classrooms

The usual expectation is that students in the first two years of school will be working on Stages 1&2 (Developing Decoding Strategies). Towards the end of the second year some may be meeting the criteria above and could be ready for Comprehension Strategy Instruction.

Students in Middle and Upper Primary Classrooms

In the middle and upper school (7-13 year olds) most students will be reading at or above their chronological age and will meet the criteria above. Whether they have a reading age of 7 or 15+,all students must work their way through Stage 3 as this is the foundation which Stages 4-6 are built upon.

CLICK HERE for our 'SharpReading Scope and Sequence' for schools where SharpReading has been implemented over a number of years.

In every middle and upper primary classroom there will be a number of student who still have decoding issues (1 or 2 years behind their chronological age is a useful marker) and will probably not benefit from the challenges of Stage 3.

For advice on what to do with these students, click on the link to "The Struggling Older Reader".